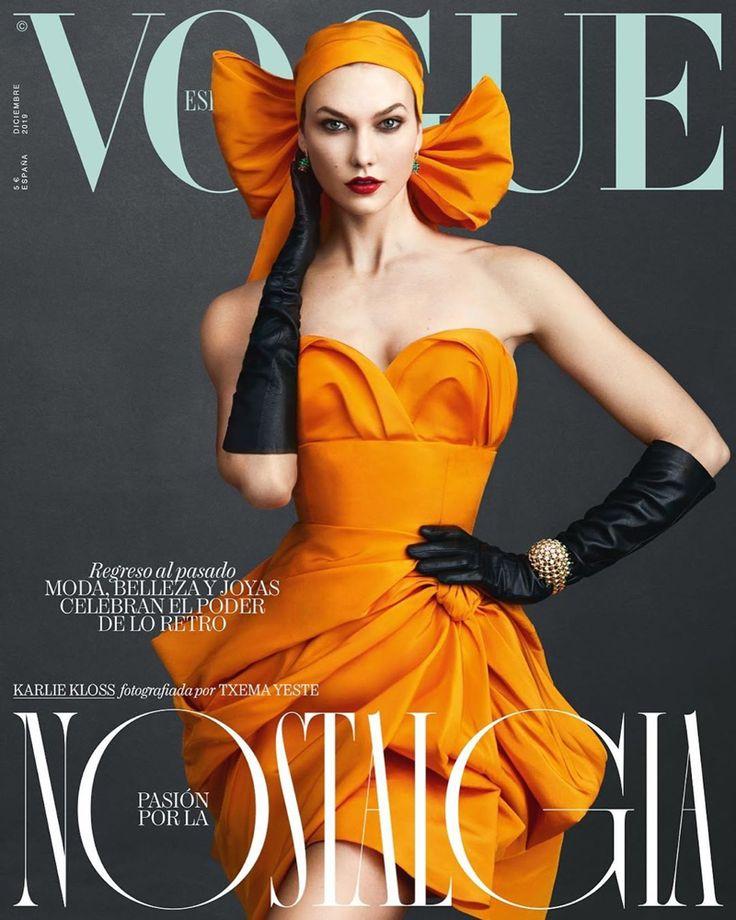

Would you buy tickets to attend a parade?|Vogue Spain Largechevron Menu Close Facebook Instagram Twitter YouTube Pinterest Facebook Twitter Pinterest Facebook Instagram Twitter YouTube Pinterest Largechevron

CatwalksLondon Fashion Week puts tickets on sale for the general public and fuels the debate on the democratization of fashion

By Osman Ahmed

A big fashion show is something truly unforgettable. Months of preparation and anticipation culminate in a crescendo of theatrics and glamor that lasts only a few minutes, but sets the tone for the new season and awakens the mechanics of desire, imagery and aspiration in fashion. Fashion shows can elicit tears of joy (as happened at Valentino's latest couture show) or spark a broader cultural conversation about sex, gender and politics (Alexander McQueen shows always strike a cultural nerve). . But for decades these shows have been reserved for industry professionals and VIPs, jealously guarded by clipboard-wielding publicists and a phalanx of security guards. That's how it has been up to now.

This week the British Fashion Council announced that tickets will go on sale for a selection of shows at London Fashion Week, with prices starting at £135 and going up to 245 for front row innings. It is the first of the "Big Four" (among fashion weeks) to implement something like this. The participating designers are yet to be confirmed, but the tickets also include access to the facilities, the round tables and the DiscoveryLAB, “an experiential space where fashion meets art, technology and music”. The news comes as brands increasingly engage with their audiences – whether it's offering in-store designer experiences or speaking directly to consumers via social media – and record-breaking fashion exhibitions in museums.

However, fashion shows remain the most visceral experience in this medium. Over time their purpose has evolved from being vehicles for stores to place orders and the press to orchestrate their advertising to monolithic marketing spectacles designed to communicate the brand's identity and promote its celebrity ambassadors. Celebrities now sit alongside influential publishers, department store merchandisers, corporate sponsors, influencers, and tech moguls. Sets range from nondescript white rooms and abandoned factories to far more extravagant: private beaches in Malibu, exotic palaces, or the gold-covered salons of Louis XV in Paris.

One thing is for sure: despite being broadcast live to the digital stratosphere and Instagrammed by every attendee, nothing compares to being there in person. Hence, there is great interest in attending.

How have fashion shows evolved in the last decade?

In the last decade fashion has become an entertainment industry, and as a result fashion shows have become more like musical concerts or sporting events than ever before. In 2016, Kanye West hosted a music and fashion event for Yeezy at New York's Madison Square Garden, with over 20,000 in the audience and a total of 12,000 models. Tickets went on sale to the public, and in addition to the third Yeezy collection, West also debuted his new album.

How to Have Good Table Manners - Table Manners & Etiquettes https://t.co/A7xWzN7xAU...#india #usa #uk… https://t.co/Qc3fPchse8

— The News Keeper Wed May 27 17:29:54 +0000 2020

In June 2018, West's protégé Virgil Abloh invited thousands of art students to his debut fashion show for Louis Vuitton menswear. Before that, in 2016, he posted an invitation to her Off-White show on his Instagram account: “The address and time are here for all the kids to come,” he wrote. Except for the fact that many were turned away due to the capacity limit. A-Cold-Wall's Samuel Ross also opened his show to the public, allowing people to register on the label's website for tickets in the hope of welcoming young people who are often excluded by the industry.

In May, a new fashion and art festival, Reference Berlin, was held in an abandoned parking lot in the German capital open to the public. It managed to bring together fashion names like Martine Rose, Comme des Garçons, 032c, Alyx and Michel Gaubert, and featured curator Hans Ulrich Obrist and Big Love Records founder Haruka Hirata. Around 2,300 people attended after requesting accreditation to enter for free. “It was a great opportunity to decontextualize what fashion brands do, and for them to get a different space to talk about their vision and experiment,” says Mumi Haiti, the CEO and founder of Reference, which encouraged designers to collaborate with artists through installations, round tables, video projects and live experiences. “Everyone who dared to participate gave us incredible feedback,” adds Tim Neugebauer, the festival's head of communication. “Getting rid of the privilege helped creative content because I had to be more creative to keep people coming back.”

What are the benefits of having fashion shows open to the public?

The question then arises as to what are the benefits of opening the floodgates. In Shanghai, the emerging talent incubator Labelhood has organized two shows – one for consumers and one for industry insiders – since it began in 2016. “Buying the clothes is not the priority,” says founder Tasha Liu, explaining that the shows are designed for KOLs (significant opinion leaders) as well as COLs (consumer opinion leaders). “The first priority is to create a community, cool people come and love the fashion they see and share the experience.” Labelhood uses the open runway concept, albeit reserved for high net worth individuals and non-industry influencers, to create demand for its emerging designers, who often cannot compete with the mammoth marketing budgets of the biggest brands. big.

“Right now there is a gap between the brand and the consumer,” adds Liu. “The original function of fashion shows was to place orders, but now they are big marketing events. So brands need to look towards the consumer. People want to be the first to see these products and design, not wait six months for it to happen."

In many cases, that kind of inclusivity doesn't come cheap. The steep ticket prices for London Fashion Week emphasize an exclusive experience rather than an inclusive one, appealing to those who want to be surrounded by industry insiders and celebrities – and can afford it. After all, if the shows were open to the public there would be less demand (and less money to be made) by those outside the industry who aspire to cross the velvet line. As long as exclusivity continues to be a prerequisite for luxury (in a certain sense, it always will be due to the price of the products), fashion will continue to be walled territory to maintain that aura of magic and mystery that arouses so many desires and aspirations.

How has couture remained exclusive despite inviting clients to its shows?

That said, consumers have never been new to shows. In the world of haute couture, consumers (or clients as they are often called) are always invited and treated to lavish events in Paris. After all, they are the ones who spend huge sums of money on the clothes and pieces of jewelry. The Cruise shows, held in remote locations and organized by the best brands in the world, are probably the most desired. Brands like Louis Vuitton, Gucci, Dior and Chanel often fly their best clients, celebrities and VIP editors to exotic locales on brand-adorned private jets. These shows are more than a highlight of fashion weeks; they offer the chance to experience a place through the eyes of the brand itself, from handpicked hotels and Instagrammable activities to a star-studded parade and after-party in a scenic location.

The invitation comes at a price — one that is charged in loyalty as well as colossal expenses. In fact, many luxury brands have stopped focusing on VIPs to focus on EIPs (Extremely Important People), with 0.001% as a priority. A personal shopper and a glass of champagne in a spacious dressing room will no longer be enough. The Boucheron jewelery house offers its EIPs invitation-only stays in its private apartment on Place Vendôme, with 24/7 butler service from the Ritz, right next door. Net-a-Porter offers its EIPs backstage access to fashion shows as well as the chance to meet designers and their buyers first-hand. This summer MatchesFashion is taking clients aboard a 1930s yacht cruising the azure waters of Ischia.

“By making the shows more open, brands have the opportunity to connect with customers (and vice versa) by creating a community of appreciation around the collections,” says Ian Grice, director of elite and personal buying at Harrods . At the couture shows in the early summer, Knightsbridge department store managed to get its top customers to attend the shows of the top-selling brands in its department stores. They also have an invite-only Instagram for their EIPs, which features their most expensive products and experiences for a selection of their customers (again: exclusive inclusivity). The appeal of attending the shows, Grice notes, is that they only happen once, making it the ultimate luxury experience, much like a movie premiere or a World Cup final. “The maneuver aimed at having more clients in the parades makes sense for everyone. It allows designers to build a community around their brand and share an experience, turning what was once a one-way relationship into a collaboration of sorts, thus building greater loyalty.”

Why is the balance between inclusive and exclusive crucial?

Inclusivity may be the buzzword on industry lips, but it is also a paradox if it is reserved for those seeking exclusivity and they can afford it. With more and more eyes on fashion and an audience more immersed in the tents of fashion weeks, the challenge is to be two things at once: open enough that it feels inclusive and closed enough that it remains. exclusive.