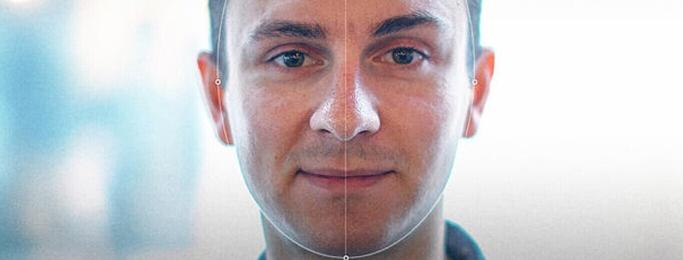

Would you sell your image so that a digital clone could be made?An Israeli company looks for models to create 'Deepfakes' and export them to third parties

They can make anyone say whatever they want. Popularized at least 3 years ago, the operation of deepfakes is complex although easy to state.

Taking a real image, AI-powered deep learning machines are capable of generating fake videos in which it is possible, for example, to see Obama calling Donald Trump an idiot.

Until now, this type of counterfeiting had focused mainly on celebrities of all kinds, from former presidents to more or less famous actors and actresses.

However, Hour One, an Israeli company, wants to put them to another use: to use images of anonymous people so that companies can generate corporate videos without the need for actors.

The company, as it has told the specialized media Technology Review, already has a portfolio of more than 100 anonymous faces. But he wants more.

To achieve this, he has enabled a casting call on his website to which anyone can apply. It is not necessary to meet any special requirements: neither to walk gracefully on the catwalk nor, much less, to know how to act.

Just send a photo. From there, the company screens based on their needs (right now there are plenty of women under 50, for example) and keeps their favorite candidates.

Hour One then uses a 4K camera to film their models making different facial expressions against a green screen background.

And that's almost all. The rest is done by the magic of the AI.

An AI can guess a person's recognized ethnicity from X-rays, and experts aren't clear why

By connecting the resulting data to software, Hour One can generate an infinite number of sequences of a person saying whatever they want in any language.

Finally, the companies choose the face of their campaign, they order the video with the text to say, Hour One does it, the client pays for them and the models take a small commission.

This, the company specifies, is measured in dollars, not in cents, but it is still not enough to live on. At most, for now, in some cases it means interesting extra money at the end of the month.

The idea, of course, is controversial on at least a couple of fronts.

In the first place, several actor unions have denounced that it is precisely these promotional videos that feed thousands of professionals who have not had the luck to become big Hollywood stars.

At street level, the debate is even deeper. How much is an anonymous face worth? To what extent are we willing to sell our face so that companies we don't even know can profit from it?

Monty Williams is seriously one of the greatest human beings on this planet. https://t.co/GgZ5JeOO2K

— Arash Markazi Wed Jul 21 04:31:24 +0000 2021

And, above all, what uses can these companies give to the image of people? Is there any legislation that limits them?

Hour One already generates deepfake faces

At 23, says Technologies Review, Liri works as a waitress in Tel Aviv, but also sells cars, works in retail and conducts job interviews online in Germany.

Liri is part of the image bank that Hour One uses to generate videos for its companies: "It's a bit strange to think that my face can appear in advertisements for different companies," he says.

Among these is Berlitz, a language academy that wanted to increase the number of videos it offered but had problems doing it with real human actors due to production costs.

Now, they say, with Hour One they are able to generate videos in minutes.

Something similar happens with Alice Receptionist, a company that provides companies with an avatar on a screen that acts as a receptionist in the US.

Hour One is updating video so digital receptionists can say different things in different languages without having to re-record hours of video.

"This seems like a pretty extreme case of technology reducing the role of humans in a particular work process," Jessie Hammerling of the Center for Labor Research and Education at the University of California at Berkeley tells Technology Review.

Sometimes, he explains, automation doesn't completely eliminate human roles in a process, but it does change them in a way that prevents people from earning a fair wage for their work.

The expert points out something obvious: if companies are going to be able to reuse the same sequence of an actor over and over again, this will reduce the demand for this type of work to a minimum.

And this, not to mention the fact that Hour One, reports Technology Review, does not allow its models to have a say in the words that will be put in their mouths or in which company they will promote.

Robots that differentiate the smell of a perfume or the taste of a good wine: 5 ways in which AI mimics the senses of human beings

And this, without taking into account another problem: Hour One, as reported by Technology Review, does not allow its models to have a say in the words that will be put in their mouths or in which company they will promote.

While these unknowns are cleared up, Liri tries to get used to having become the image of various advertisements.

"Some friends have sent me videos showing my face, which I found very strange," he says. "Suddenly, I realized that this is for real."