Traveling to India was a great gift, a mirror that that country put in front of me

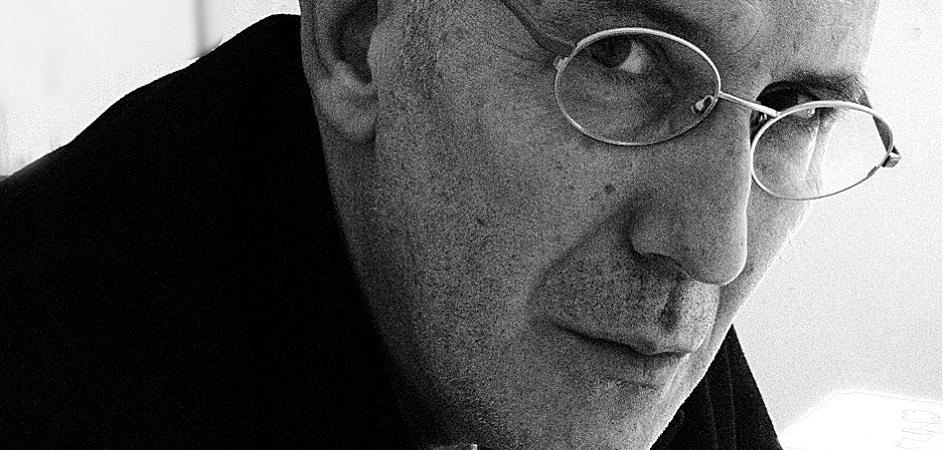

I met Óscar Pujol in India in 1996. Until then I was an admirer of the articles he wrote in Altaïr magazine, where the life, rituals and art of India were woven into a skein brimming with meaning.

Óscar had been studying Sanskrit for ten years (of the 16 that his stay lasted) on a scholarship at the University of Varanasi. He lived with his wife Merce and his son Vasant in a modest home. I still remember his words when he opened the door for us: Who are you?

Many years later we met again, this time together presenting a monographic magazine on North India at the Altaïr bookstore. At that time, Óscar was finishing his magnificent Sanskrit-Catalan dictionary (which gave rise to his work in Spanish Sanskrit-Spanish Dictionary: Mythology, Philosophy and Yoga) and he was the director of studies at Casa Asia. The publication of that work marked a milestone in his life.

Today he is the director of the Cervantes Institute in New Delhi. Talking with him, during a fleeting visit to our country, was a luxury. Óscar is now almost a pandit, the quintessential Indian scholar; and he has continued to bring Hispanic and Indian cultures closer together through works such as Yogasūtra (or Los aforismos del yoga) by Patañjali or La Ilusion Fecunda. The Thought Of Samkara. But his love of life and his involvement in it offset his passion for libraries.

A trip that changed his life

-Did you feel a crush on your first trip to India? -No, it was more of a gradual attraction. For me it was a destination like any other. I traveled in 1979 with my future wife and we were lucky enough to be able to stay for a whole year. I arrived with the typical apprehensions: the first few days I washed my hands every ten minutes. But then we had a very calm and pleasant trip; We spent more or less a week in each place: Agra, Varanasi, Bodgaya... After two or three months I began to feel a very strong attraction to visit temples, to discover a universe that I totally ignored.

Related article

Paradise is near: how to see it?

– What surprised you the most? –The fact that people believed in something beyond the palpable, that eye open to the intangible. And that kind of comprehensive acceptance of reality. We are always trying to modify reality, or have a version of it through abstraction, art, technique, the camera... Wanting to capture a comfortable and attractive part of reality for our interests. I was impressed to see how certain people did not try that, but accepted reality as it is.

Resignation exists and in abundance in India. But at the same time that there is resignation -which for me is not Indian fatalism but the result of very harsh social conditions that you cannot change as an individual-, there is acceptance, which is the opposite.

Resignation is passive, you are conditioned by circumstances beyond your control. But acceptance is active, that is, you recognize reality as it is, you recognize yourself, your limits... and you accept them. Assuming the limits means trying not so much to overcome them as to be yourself within them. The acceptance, that saying "the world in a certain way is now perfect but I don't realize it because of my ignorance", amazed me.

What changed after that trip? -In the last months of the trip I realized that I was not a man of action or an adventurer, but of study and reading. And I left India with a very strong desire to go back to university. It was like a great gift, a mirror that that country put in front of me: stop traveling, study, concentrate, because you are a man of letters and you cannot run away from yourself.

A verse of the Gita says just that: discover your own personal dharma, that is, who are you, what do you like, what are your faculties. If you don't discover your own dharma, you don't turn the wheel of the world, you are on the sidelines, you waste your life. Participating in this turning of the world is a kind of cosmic sacrifice. I believe that we have a very specific function to fulfill and that we spend our lives trying to discover it. If you are lucky enough to discover a part of what you have to do, your life changes completely, you find meaning in what you do, even if you have difficulties.

–And that's how you discovered your vocation for Sanskrit? -Yes. I dropped out of Philology, tried Philosophy, and decided I had to go back to India to study Sanskrit. I did not achieve it until 1986, after a trip in 1984 in which everything went wrong for me.

–What makes Sanskrit more unique for you?–The richness of its literature. You have poetry, logic, mathematics, grammar, eroticism, mythology... There is no branch of learning in which there are not interesting thoughts in Sanskrit. And it is very plural: you can find texts against vegetarians, written by Bengali Brahmins. That variety, and above all the subtlety of the arguments they use, makes it fascinating. It is a very flexible language, very plastic, with three thousand years of literary tradition.

I consider it a monument to human intelligence, just like Latin and Greek. And since it is highly cultivated by the Brahmins, who have dedicated themselves to it in a very professional way, it has reached unprecedented heights of refinement. She is very beautiful to sing and recite and I think she has a great future... This goes to my friends from the University of Varanasi who are not very excited...

–Has Sanskrit given you many things on a vital level?–Yes, many. It is a language that you can learn, I recite it every morning. You have verses for everything, from when you wake up to when you go to sleep. You salute the earth and ask forgiveness for stepping on it when you get up... A genuine Brahmin lives all day in a certain way with Sanskrit resonating within. He has a melody there that accompanies him and offers him verses for every occasion.

There is a language deficit in our society. I think of all the verses of popular wisdom, in the proverbs, all that we have lost. We no longer have Castilian within us, only remnants. And one has to carry his language on his back, because language is the intercessor between the everyday and the absolute.

Understand the Indian way of living

–Is there an Indian art of living?–Yes. On a more superficial level, it implies taking great care of the people who live with you, starting with the family, and respecting your emotions. Emotion is like a river and it comes from somewhere. Each family, in turn, would be like a stream. It is born at a given moment, and then that emotional current is nourished by the hundreds of places through which it passes. You are one of those water stations. People are constantly looking for their origin in strange beings, acquaintances that seem to have just fallen from the sky, without paying attention to that emotional current that drives them from birth.

The Indians may have friends as close as the family, but they do not neglect the family or substitute friendship for family ties. Respecting emotions and not being too hard on oneself or others would be perhaps the first Indian art of living. The Indians consider that the mind is material, they live a continuity between mind and body, as the name of your magazine suggests.

–What qualities embody the three main deities of the Hindu pantheon?–Indians worship Shiva and Vishnu but not Brahma. For them Vishnu or Shiva is the entire trinity. There are three basic deities: Vishnu, Shiva and the Goddess. Brahma is the creator; Vishnu the preserver and Shiva the destroyer. But if you believe in Vishnu, he embodies all three functions. The Goddess does the same: she can delegate to Shiva to destroy, but the essence of the three functions is in her.

There is a type of meditation that consists of observing the creation of a thought, the moment it lasts in your mind and how it disappears. This is already observing samsara: a constant cycle. From here it is about perceiving that everything is impermanent, except the consciousness that observes.

Related article

Discover mindfulness meditation to live without stress

–What is time for the Indian cosmovision?–The Yoga-sutras say that time is a mental creation. The world does exist, it is not an illusion. There are two things: consciousness, which is spirit, and the material world. Consciousness observes the world, and by observing it, the miracle of creation and existence occurs.

Matter is made up of atoms according to a very old theory in all Indian physics. As atoms move in space, reality is constantly changing. There are only instants, but not time. An instant is the time it takes for an atom to move from one point in space to another. The mind can observe these moments. What does not exist is the succession of them. Kant also said it: only the instant exists. All the rest are mental constructions that give a sense of continuity.

Related article

Traveling to sacred places: the encounter with oneself

Surya, the sun. What can we feel when seeing it rise from the banks of the Ganges in Varanasi? - First of all, it must be said that it is incredibly beautiful. Beauty awakens a series of feelings that make you transcend your daily misery a little. The sun rises in the morning in a certain way to indicate what a beautiful Sanskrit verse says: that each day is unique and you can give it the best of yourself. The sunrise is like the creation of the world. When you wake up you enter the scene and have the opportunity to participate in the creative task until the extinction of the world, which will be at night, when the sun retires to sleep. Beyond the sensations, the beauty of the light that is reflected in the water, in the reddish walls of the palaces and temples, the songs... the sunrise is accompanied by people bathing in the river and all activity.

In the ceremonies water is offered to the sun in the morning and that is very important. Every start involves danger, and it is said that the rising of the sun is a critical moment, because it is attacked by millions of little demons of darkness who try to prevent its departure. The offerings of water that are made to him are like weapons, like mantras, that shoot out and try to eliminate the influence of those demons.

Whoever collaborates in these rituals is not a passive spectator: he helps the sun rise, which makes him a participant in that creation process, which is not unilateral. People make a sacrifice, perform a ritual, say a prayer, to help the world keep rolling, the sun keep rising and the wheel keep turning...

-What attitude do you recommend if you attend a cremation? -Attentive and concentrated reflection. I think there is nothing more uplifting and profound than watching a cremation, especially in Varanasi, where there is no sign of pain. You sit there, I did sometimes, like many Indians and Westerners, to watch the body burn.

We only know one real thing and that is that we are going to die. We don't even know if the sun will rise tomorrow, because there may be a cosmic cataclysm. For me, cremation is a lesson in reality: thinking, meditating that you are going to be that corpse, that thing that is stretched out there, that is first soaked in the river and then wrapped in a cloth, surrounded by your children or your loved ones. ... Then you see the flames arise and how nothing remains of the physical body...

It is said that it is easier for the soul to emerge from a burned body than from a buried one. In Sanskrit dying is called "returning to the 5 elements": pañchatattva or pañchabhuta (five elements) gamana (return). Cremation facilitates that dissolution and the passage of the soul to whatever it is. Another thing that draws attention in Varanasi is the great transit of corpses.

Sometimes they are carried on a tricycle, and they seem to tilt their heads as they rattle, as in last warning. I was once with my wife and son in a richshaw behind a cart with a dead body. It was summer, we couldn't pass it and the stench was unbearable. At one point I couldn't take it anymore and told the driver to stop so that at least I wouldn't be behind. But that smell permeated me all day.

In the end I saw that the difference between me and the man who was in the cart is the same as between the person waiting in line and the one who is getting the movie tickets. It is a matter of minutes, hours, days, years, but we are in the same queue. By attending the cremation it is possible to identify with that corpse, even if it is very hard, and from there to think about what we are doing in our lives and to what extent it will be of any use to us in the end. Everyone has their answer.

–What would you advise when visiting a Hindu temple?–First, do not step on the threshold. Then, don't go in empty handed, bring something - a garland of flowers, some kind of offering - and ring the bell, announcing your arrival. The threshold is an intermediate zone between two worlds and it is considered unwise to step on it, as it can reject you. You have to greet with a reverential gesture the protectors of the threshold, two deities normally located at their sides -if you want to be received by the director, it is better to ingratiate yourself with the doorman-. Once inside, maintain a respectful attitude when making the bypass.

–The Hindu holy man, does he exercise a vocation of spiritual search or a simple trade? -Both. A study stated that 25% were mere charlatans. It seemed like a low number to me. But the admirable thing is that there are authentic holy men, capable of leaving what everyone is after and trying to achieve something else. Ortega y Gasset said that the modern State is absolutist: it prohibits you from one thing to another and ends up interfering in all facets of your life, even in your personal search for wisdom.

The State will say that it is not possible to live in the naked forest, that only makes a madman, and will send its social agents to prevent it. But in India someone suddenly stops and people begin to adore him, even if he is gone, because he is a symbol of someone who has gotten out of the rat race in which we all walk, beset by mortgages, by work, for the crisis. Knowing that we have no escape and that we must try to survive with the rules of the game. But to think that you can stop everything and that there is another way to live, that in itself is already great.

Related article

How much do you give to life? The power of the offering

-India, the country that invented chess, also enunciated the law of karma... -That's true. Chess leaves you a space for decision and shows you that everything is connected. There is only one distinction, that in chess all moves are causally determined. Karma is also causally determined, but at a given moment it can be dissolved by an act of knowing. In chess that would be equivalent to throwing the board to the ground and stop playing...

You can have very negative karma, and reach a point in your life where you understand a number of things, then that karma remains merely residual.

India as a cultural melting pot: issues of coexistence

–What is the difference between having lived in Varanasi and living in Delhi now?–A lot. At the moment in Delhi it is perhaps where most attempts are being made to make the dream of Indian modernity come true. A lawful dream, of having a country that works like the modern world. Delhi has gone from 5 to 16 million inhabitants in recent decades. Its car park exceeds Bombay, Calcutta and Madras combined. All countries and major international diplomatic institutions are represented in Delhi.

As director of the new Instituto Cervantes I lead a very different life from that of a student in Varanasi. Austerity and concentration are necessary for a life dedicated to study. Now instead it is necessary to plan, negotiate and socialize. In a comic key I could say that I live without being able to break the cold chain. I often have to wear a tie and a jacket in 40º C. That requires being in air-conditioned rooms and going out and taking a taxi that also has it on the way to the next meeting. Executives don't sweat!

On the other hand, Delhi is today a culturally very cosmopolitan city. The offer is very varied: from Indian classical music, both North and South, through dance and theater in Hindi, in English and sometimes in other Indian languages, to Russian ballet, Western classical music, jazz, flamenco, European or Latin American cinema cycles or Mexican crafts... The cultural sections of embassies from all over the world compete to show the new capital of an emerging power the charms of their respective countries.

–Are the castes undergoing transformation? -It is a very complicated issue. Castes have existed everywhere, although perhaps not so systematized. Equality is a very recent achievement. The usefulness of the castes is that they provide an identity, not centralist, but locally diversified and deeply felt. There are rooted rites there, a way of seeing the world, an integrated society that can include thousands to millions of people. What would you be if your caste disappeared? The option offered by the modern world is nationalism: you will be Indian, as is happening, especially in the cities and among the young. That is to say, you will be Indian against the Pakistani, against the Chinese, you will have an army, you will want India to triumph...

The caste brings a very clear local identity and incredible group solidarity, which gives a lot of security: even if your caste is poor and oppressed, you are not alone. Thanks to them, India is a pioneer in inventing methods of social protest, not just the hunger strike. If the sweeper caste of a farming community did not receive enough surplus food, they stopped collecting the garbage and that was effective, because there was no one else who could do it.

There has always been an internal rebellion in India against the oppression of castes and groups that have tried to abolish them. Buddha for example, and many others. But those reforms have ended up becoming castes in themselves.

As bad as they are, the system has allowed for diversity in India. The brahmin does not want the outcast to be like him, and vice versa. Bans and codes from one group do not affect neighboring groups. But there has been an incredible historical rise in low castes and untouchables. And the tendency to keep privileges for the upper castes. That's the terrible thing. The combination of democracy and caste has led to lower castes now being in power in India and that paradoxically is perhaps underpinning the caste system.

– How do you see the tension between Hindus and Muslims? -It's getting worse. The miraculous thing is that they coexist from the outset. An iconoclastic religion and another with thousands of images, for which worshiping a single God can constitute a poverty of worship. They are opposite religions, but they coexist, even sharing parties. The problem is the creation of ideological superstructures on top of religion. In fact, the more local the religion, the more tolerant it is, since it forces you to understand your neighbor. But now the prevailing voices are not local, but transnational.

There is an ideology of international Jihad, very present and contrary to the Hindus, and also a national-Hinduism, which is racial and seeks to standardize all of Hinduism: a single book, a single practice... Neo-Hinduists are very intolerant of Muslims . It's generational: those over 50 are usually tolerant while younger people are more impatient and intolerant, and that's scary.

Related article

Bhagavadgita: The Instruction Book for Life

–Is Spain known in present-day India? -Spain is fashionable in India, and that is new. One of our challenges at Cervantes, apart from teaching Spanish and the other languages of the country, is to give a consistent and up-to-date image of Spain. When the Indian discovers the Spanish culture, he tends to identify himself very much with it. Olive oil has become fashionable, which until recently disgusted them and they only used it for massages. The Hindi newspapers, I am not telling you about the ones in English, recommend taking a minimum of one liter of olive oil per month, and that costs ten times more than the oil that is normally used. Companies like Roca and Keraben succeed.

There is a notable interest in Mediterranean cuisine, and also confusion, since they believe that one of its typical ingredients is the jalapeño pepper... We are at a time when it is interesting that they know us better. It is my function there. And that can be very good for Spain. The Indian and Mediterranean worlds were connected in the 9th century BC. C. Anglo-Saxon culture is more foreign to them. Over there I think there is an important dialogue, that everything remains to be done at many levels between what we would say the Mediterranean and India.

–How is the Cervantes Institute doing?–There is great interest in the Spanish language and Hispanic culture. The Indians discover the Hispanic world as a more accessible and closer West. It is something relatively new and we do not know the scope that it may have, but it is something that the new Cervantes Institute will promote in New Delhi. At the same time, Spanish in India is still a long way from being as important as German and French as business languages.

– Is there a difference in the level of education in Spain and India? – I think that the level of certain private secondary schools in many cities in the provinces of India is today higher than that of the best Spanish schools. Primary and secondary school have entered a deep crisis in Spain, just as they entered the United States. I was surprised by the really low level of general knowledge of a first-year student in today's Spanish university. Not everything is bad, obviously. The Spanish student has more refined instruments of criticism and dialogue and reasoning than the Indian. But, as an Indian friend said, he has them but it seems that he doesn't use them, that he doesn't know how to use them or that he doesn't care.

The Indian university is very hard, it requires a lot of brainstorming, and sometimes there is a lack of creativity. The average Indian student has more information, is harder, more disciplined, he can take some exams at a level that is difficult for the Spanish, but in general his writing is less incisive. Now, there is an elite in India that has a lot of information, has cultivated memory - because they do not despise it as an instrument of learning - and at the same time they are extraordinarily brilliant at a critical level. They are the engines of Indian growth, and the ambassadors of India as an intellectual powerhouse.

Ortega y Gasset spoke at the time of a misunderstood equality, equality by the lowest common denominator, which is achieved based on a gradual decline of the whole world: as everyone does, it is equality. But the desired equality would be the opposite: a rise of all upwards, and not a general decline, as sometimes seems to happen in some areas in the West.

–What would you advise to those who travel to India for the first time? -Patience. And do not look for what he already has in his house, even if it is with a little more spices, condiments and exoticism. If in the face of a setback patience is not enough, then getting angry, complaining, crying... all this is useful. Indians love to be told stories. If you are really able to tell your story, you get what you want. On the other hand, the ancient hospitality towards the traveler is still present in India. The Indians are skilled at pushing you to the limit; until when you are desperate suddenly everything is solved. The Indian is very communicative, he does not understand shyness. There is no worse thing than being shy and sad in India. So let's put a little patience in the luggage, a little fable, and let's do theater so that we can be better understood. The seasoning is important: the Bollywood industry does not produce its films without putting masala (mixture of spices) into them.