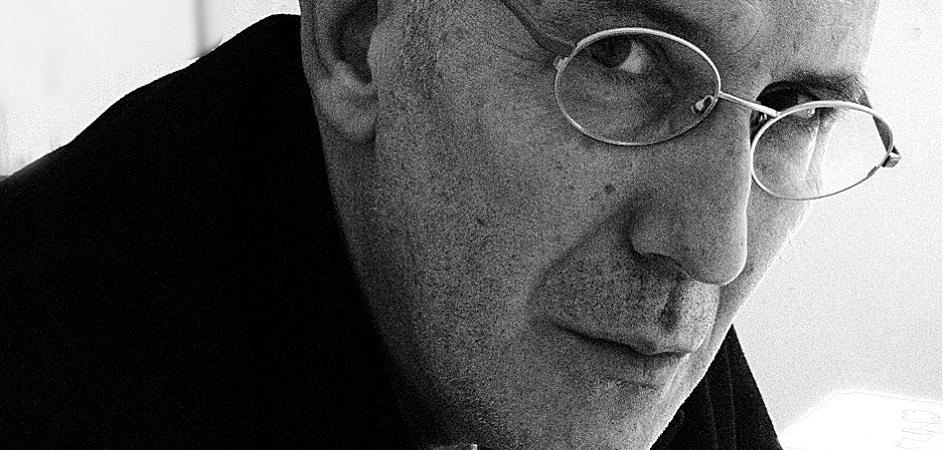

The man who "invented" the Centennial and made La Plata ride in a Buggy - General Information The man who "invented" the Centennial and made La Plata ride in a Buggy

Juancho, is it true that you were once an actor in a very successful Mexican novel?

The chronicler, already almost a friend after having written dozens of notes about his gastronomic undertakings on the Centennial road, with Mapuche at the head; of his forays into the automobile world with the invention of the Buggy Puelche, the first one hundred percent car from La Plata; or of his incredible adventures in the Aztec country, he knew a thousand anecdotes of that man with white hair and a frank smile who invited him to eat with a good wine in between to tell about his life in a movie. But that of the Mexican novel was little known.

“Yes, haha, I did that too” , said Juan. “It turned out that one day, while I was at the airport in Mexico, a guy approached me to ask me if I was Argentine, and when I said yes, he asked me to work in a telenovela. I started laughing and told him that he wasn't an actor, but the guy insisted, 'it doesn't matter, he said, we need someone who looks like him and speaks Argentine.' And I, who was not disgusted by anything, began to pack myself. To make it short, the novel lasted five years, broke all the ratings of Mexican TV and in the last chapter the President of the Nation even acted. Later they offered me to pursue an acting career, but the truth is that I was bored having to study neutral language, and I dropped out. I preferred to continue with gastronomy, which was my thing” .

And boy was it his thing. Juan Arturo Garbarini was born in Chascomús, but settled in La Plata when he was 8 years old, and at 24, while he was an architecture student at the UNLP, he had the idea of opening “Morocco” , which was the first nightclub on the Camino Centenario, an enterprise That would be followed later by bowling alleys like “Mapuche” , “Pancho Villa” and “Napoleón” , all with his signature.

It was the end of the 1960s when, on that dark road that led to Buenos Aires, the La Plata scene broke out first with Morocco and later with Mapuche.

More precisely, it was on July 18, 1969 when Mapuche opened its doors, the year in which man would travel to the Moon; Students would be crowned for the second consecutive time as Champion of America; and Pochola Silva's headband was already a symbol of La Plata.

It was also the time of the sweet and savory waffles, from Torinos Comahue; of the carnival dances in Estudiantes and Gimnasia and of the meetings in the Jockey Club. Because all of this, in one way or another, passed through that bowling alley on the Centenario road, at that time still narrow and with dirt shoulders, almost deserted, which would mark an entire era in the City.

“The truth is that it was an absolute novelty for La Plata -Juan said- because in the Centennial there was nothing, not even light, but quickly the bowling alley had such an angel that the most important personalities of the City became regulars of the place, and it could be said that there are no Platenses of those times who have not had something to drink in Mapuche at some time” .

In those talks with Juan, his face lit up when he talked about Mapuche. “In 1966 I had inaugurated Morocco, a disco that worked on the Centennial road between 501 and 502 until it burned down in 1972, and Mapuche was the ideal complement. On Fridays, Saturdays and Sundays it was religion to go dancing to Morocco and take a submarine to Mapuche. And when Morocco disappeared, the custom of going to the Mapuche continued” .

Juancho was already over 70 when those well-watered talks were given, and he had returned from Mexico, another important chapter in his novel life, but when his mind traveled to those 60s he was once again that young man full of projects, and he was able to talk for hours at a time about it.

“I had a total of 38 names to baptize the bowling alley -he exultantly recounted- but I leaned toward Mapuche, which is an indigenous voice from southern Argentina that means native to the place. And the bowling alley was well made of the place, it had no competition. Later, in 1975, Vialidad expropriated a part of the land to widen the road; in the year 77 another bowling alley called Sausalito was inaugurated, and on August 7, 1979 I opened Pancho Villa on the same Centennial. The scene was already installed there” .

At that time, between 1978 and 1982, that bowling alley had the luxury of having a branch in the Center, on Calle 7 between 48 and 49, which was called "Mapuche Center" , although the touch of distinction was still given by that of Gonnet.

"It's that very strong things happened in Gonnet -Juancho recalled with his usual smile- more than once I met young people who told me 'in Mapuche my father proposed to my mother, and there I also got groom'. That is very strong” .

It is that that emblematic bowling alley of the Centennial would mark a course forever. In its years of splendor, it opened its doors at 8 in the morning and closed at 3 in the morning. It was a restaurant, cafeteria and bar; and on Fridays and Saturdays the scene continued there until after four in the morning, when parades of models that hadn't even been announced took place on its floors.

“I was born when Mapuche was already a year old - says Valeria Garbarini, Juancho's daughter - and I remember that the Centenario was a dark, one-sided street, with a few lanterns hanging from the wires. I grew up with the Mapuche fury, when cars were parked on the shoulder, when artists like Jorge Porcel and Moria Casán came, when they ate sweet and salty waffles at all hours, which was a dough based on flour and egg with accessories to choice above. It was a very nice time that in La Plata with which I grew up " .

THE PASSION FOR THE IRON AND THE FUROR OF THE BUGGY

But was Juancho just that? A guy capable of creating successful ventures from nothing that would mark an era? Yes, it was that but also much more. And it could even be said that the bowling alleys in the Centennial was just a sample of what he could do. Because his true passion, in reality, was “the irons” .

“I liked cars since I was a child -he said- so much that when I was six or seven years old I told my old man, who was an electromechanical engineer, that I was going to have a car factory, imagine how he laughed. But I was serious, and in the end I got away with it, because he would end up developing the “Buggy Puelche”, a car that was built from the engine and chassis of the Renault Gordini. And the little car became fashionable, as they began to buy it not only in La Plata but also abroad, to countries like Bolivia, Chile and Costa Rica” .

Those were the early 70's, and what Juancho told was not fantasy. From La Plata, more precisely from a small workshop installed in Gonnet, the guy had set up a factory with which he came to sell about 1,500 units of the Puelche, a car that a whole generation of people from La Plata dreamed of, longing to get on it for a ride. along the beaches as did the models and celebrities that Juancho himself hired to promote the product, such as Teté Coustarot and other “top” models of those high-voltage years.

“In the fury of Mapuche were artists like Jorge Porcel and Moria Casán”

To say that there was a car created and manufactured in La Plata would seem unreal and impossible today. But it was like that, and such was its success, that even the "formal" automotive industry began to look at it with suspicion.

https://t.co/3rJqzVyGES

— ﺡ Wed Dec 02 10:10:27 +0000 2020

That was a crazy dream that saw a splendid dawn in those 70s, but shortly after it was locked in the night of a country with a brutally fragile economy, although that reality still rolls through the streets of La Plata today, owned by collectors who still they keep impeccable units of those buggys.

However, almost at the same time, Juancho was about to touch the sky with his hands when another of his projects, the "Iguana", reached the ears of the highest priests of the Renault factory and was very close to becoming an international car but manufactured in series for everyone.

Because it was the president of Renault himself who was enthusiastic about that car to fill the gap left by the cessation of production of the Gordini and the need to do something different with the Renault 4 L and 6 of that time.

“In the year 66 he had inaugurated Morocco, a disco in Camino Centenario between 501 and 502”

During a trip to the north of our country, Juancho had been amazed seeing how a small lizard would sneak between the stones and the bushes, agile and enduring under the sun, and he told himself that he would go to that project that he already had in mind. to call "Iguana".

And so it was that the plans for the Iguana reached the desk of the top boss of Renault, who connected with Juan and asked him if he already had a prototype of that car.

Far from being disturbed by the call of such a world businessman, Juancho was not daunted and with the coldness of a poker player he answered yes, that in about 20, 25 days, he would have a prototype ready. That was a lie that would have to be backed up, because Juancho had nothing but his ideas, and for that he summoned his faithful adventure lieutenants to shut themselves up in Gonnet's workshop for days and nights to assemble the prototype. And they did.

The description of that vehicle from La Plata said that “the interior of the Iguana, fully upholstered, presents a sports dashboard of exclusive design, built in one piece; specially designed duralumin steering wheel with padded grip; Complete easy-to-read instrumentation and lever to the floor with short and precise travel . And in France they liked it so much that that car manufactured in Gonnet was going to be sold through the network of official IKA-Renault dealers, and even had orders from Uruguay and Venezuela.

“When I was six or seven years old I told my father that I was going to have a car factory”

Juancho's project advanced elbows in the midst of an already fragile economy that would break into a thousand pieces shortly after with a phenomenon remembered as "el Rodrigazo".

With bitterness, Juancho recalled in those endless talks that “bad politics and bad economics forced us to close the factory in 1976, and for all of us it was a wound that still bleeds. But it comforts us to see that the result of that work is still valid in those who carried these cars in their hearts” .

MEXICO, THE RETURN AND THE GOODBYE

After that bitterness, Juancho Garbarini decided to leave the country for Mexico to start new dreams.

“I lasted until 1988 and left -he said- I had a friend from La Plata who was living in Mexico and was planning to open an Argentine restaurant in the Federal District, and he wanted me to advise him. In the end, I ended up doing 23 restaurants for third parties in that country, providing gastronomic advice and design, and apart from that I created restaurants for myself” .

One of them was the “Coffee West”, which in Mexico became a shelter for many Argentines, and especially people from La Plata, who required a helping hand to embark on the wonderful adventure of seeking a new destination.

"They offered me to pursue an acting career in Mexico, but the truth is that I was bored having to study neutral language, and I dropped out."

“When dad returned from Mexico I already felt that he was ill -recalls his daughter Valeria today- he already had a basic illness, and wanted to continue working, dreaming as he did all his life, but his health no longer he allowed it. He left us at the beginning of the pandemic, and I was with him until the end. He was everything to me, an entrepreneur who left me several legacies, an ever-present father who, with a coffee in between, encouraged me to move forward with any project, because he was a dreamer who always instilled work in me above all else. He was my dad, but he was also a great friend."

Juan Arturo Garbarini was born on December 15, 1939, son of the engineer of the same name and Blanca Rosa Bottino Camillión. He married Ana Abella Di María and had three children, Valeria, Paola and Juan Manuel, who gave him two grandchildren, Mauro and Belén.

Juan Arturo Garbarini, el Juancho, passed away in La Plata on June 24, 2020, and left the magic of his crazy dreams, which remained forever floating in those who had the fortune to meet him and share his adventures. They knew about him from Enzo Ferrari, whom he visited at the Maranello factory, to legendary car designers such as Pininfarina himself.

But before he left, he knew a small satisfaction. His cars, those made in the 1970s at the Gonnet Workshop on Camino Centenario and 511, were declared of "cultural interest" by the Deliberative Council of the Municipality of La Plata. But more than that, he also knew that his dreams, his undertakings and his novel life, were also the heritage of all the people of La Plata.